In the Shadow of Carnival

How I came to appreciate the dancing (semi) naked ladies.

My parents would always compare it to Mardi Gras. Except, they said that, in comparison, Mardi Gras was like a “Sunday School picnic.”

To avoid contact, churches in Brazil would plan spring retreats. They would just happen to be right before Lent–usually the weekend before. You might think that this is due to the holy nature of Lent and the time it allows for personal reflection and sacrifice. They might claim that is what it was for, but it had more to do with avoiding the event that shut down the entire country.

Carnival.

An event that officially begins the weekend before Lent, but over time, has started earlier and earlier.

This event includes concerts, block parties, expensive private parties, dances, drinking, no sleep, and the most important event of all: the competition of parades that the different Escolas de Samba (Samba Schools) participate in.

The mind of the church thought it was in the best interest of good Christians to be secluded on a campground somewhere away from the city. The goal was to isolate people, preventing them from being tempted to participate in, view, or enjoy any part of Carnival. And what better way than to have a religious retreat?

I grew up in the mindset of that culture and even attended some of these camps myself. It was always made very clear as to why we were leaving the city: carnival was sinful–it was a carnal orgy that was to be avoided at all costs. The years we did not go to camps, my sister and I were not allowed to watch TV in the evenings because everything was televised during prime time: the parades, the parties, the concerts, a bacchanalia that would damn my soul straight to hell if I even caught a glimpse.

As much as we were shielded from the sins of carnival, it was impossible to avoid. Carnival was everywhere–stores would decorate in bright colors, we would get time off from school1, and there were billboards and commercials on the radio, all advertising the year's largest celebration–you could not escape it. The hypnotic drumming accented with the sounds of the cuíca and cowbells on every radio station managed to seep in, regardless of how protective my parents were.

As missionary kids, we were insulated from Carnival to the best of my parent's abilities. It was confusing, though, because while my parents would not let us watch it, they recorded some on VHS to show people back in the US. They bought records of Samba music so Americans could better “understand” Brazilian culture. But yet, we were not allowed to watch it on TV. My dad would tell these apocryphal stories of how the TV camera operators would lay on the ground to be able to get more provocative shots. All missionaries I encountered in Brazil treated the entire celebration as a foreign oddity and pariah instead of the cultural phenomenon that it is.

As an adult, I get this feeling every spring, a feeling of desire and longing. A feeling that something is bubbling up from the recesses of my memory and trying to get to the surface. When I get that feeling, I know that Carnival is almost here. I don’t do anything special to celebrate, but I do make sure I watch the parades every year. I subscribe to the Rede Globo streaming service and watch their full coverage. The coverage that I was not allowed to watch as a child. I watch the parades from São Paulo, the concerts in Pernambuco, and the main event, the parades in Rio de Janeiro.

The major cities of Brazil have multiple Samba Schools–every school has around 3000 people participating in the parade–people of every color, gender, age, body size, and ability are represented. Contrary to popular belief, the Rainhas (Queens, AKA scantily clad women) are not all slender and big-breasted–they also run the gamut of sizes. There are even alas (groups) made up of children. Carnival is indeed the great equalizer; people of all levels of society, all incomes, and all ages come together in a single place.

If you were to ask any Brazilian the one emotion they associate with Carnival, I can guarantee the answer would be happiness. Carnival is about enjoying the moment, letting loose, and being free of the hardships and monotony of life, even for a fleeting moment. It is a time to find happiness and joy in the music, dancing, lights, costumes, and colors. Of course, due to the yin-yang of life, Carnival has a dark side, and Brazilians will readily admit to it and not try to hide it. During the Carnival season, people drink in excess, crime goes up, and, unfortunately, the death rate also rises. Even with its darker side, the celebration always outweighs the darkness.

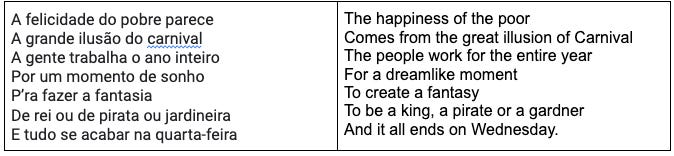

Antonio Carlos Jobin, known for his song, The Girl from Ipanema, wrote a song called A Felicidade (Happiness). It is a beautiful yet sad look at the ephemeral nature of Carnival. There is a verse that, roughly translated, says:

People prepare and look forward to that one hour, where they sing, dance, and exude happiness as they march down the half-mile parade stretch. And when it is over, they immediately start planning for the following year.

I don’t know if it is because I am older or maybe the things I was “protected” from as a child were exaggerated, but as I watch Carnival as an adult, I question what is so bad about it. Yes, there are scantily clad women, sometimes topless–but there is more to it than just that. The scantily clad women are just a fraction of the entire experience. But from how my parents would act, I’m unsure what I imagined. Maybe hundreds of topless women gyrating to the beat of the drums? But the semi-nudity is what my parents latched onto. In reality, there are more fully costumed dancers than there are half-naked women. As an adult, I have been able to step back and see the larger picture, and I can enjoy the parade for what it is–a celebration of life, vitality, and the moment. I would like to think my parents are able to see Carnival like I do now. I don’t know— maybe they were influenced by their jobs as missionaries or maybe by others around them. Perhaps they felt their choices were the best they could do.

Asher and Amanda watched the parades of São Paulo’s Carnival with me this weekend. These are the precursors to the big Rio de Janeiro parades. Until this moment, I didn’t realize how much I enjoyed sharing this part of my upbringing with them–but at the same time, it really isn’t a part of my childhood. I feel like I am making up for lost years. I know enough about the parades to explain the main points to them, but at the same time, I’m still learning and understanding different elements. I’m translating for them; we are all trying to figure out the theme and how the different groups represent it. We comment on their costumes and what we like and don’t like. We also laugh at the silliness and absurdity of some of the groups. We praise the colors, the feathers, and the ornate and lavish outfits. We are amazed at the 2 to 3 story floats and how they shake up and down from the movement of so many people on them.

I have spent the last few days watching and enjoying the coverage of São Paulo and Rio’s Carnival. I think I am safe from condemning myself to hell for watching people dance, even the semi-nude ones. Every year, I watch the parades, celebrating in my own quiet way and sharing this with my family; I am less conflicted and more empowered. I shed the feelings of guilt long ago, but the damage that religious absolutism did to my own life has taken longer to heal.

As we watched the parades, Amanda, with that knowing gleam in her eye, looked at me and said, “We are going to have to go to Rio one year for Carnival, aren’t we?”

I just smiled at her, but my heart did a little samba as she said it.

It is interesting to note that I attended a Christian school for part of our time in Brazil. They also gave us days off for Carnival—maybe so we would not miss school attending the church retreats?